The concept of a dance show set to Leonard Cohen’s music was approved by the man himself when it was first conceived by then artistic director of Ballets Jazz Montréal, Louis Robitaille. The Canadian singer-songwriter requested the inclusion of more recent songs as well as the iconic…

Used to Be Blonde ★★★★

Review: Pinocchio ★★★★ - Israeli-born choreographer Jasmin Vardimon and her company create breath-taking stage pictures to enchant

If you want to introduce your child to the magic of live theatre, then the captivating combination of physical dance theatre and brilliantly imaginative staging with which Yasmin Vardimon and her company weave the story of Pinocchio should leave any theatregoer, new or experienced, eager for more.

Vardimon has an extraordinary imagination and with her collaborators, set designer and dramaturg Guy Bar-Amotz and lighting designer Chahine Yavroyan, she finds a fresh way of conjuring each scene in Collodi’s story of the wooden puppet boy who yearns to be a real boy. Perhaps the most distinctive signature of her style is the stunning and seamless way her eight performers work together to use their bodies – or often just one body part each – to create a whole.

Working together with precise discipline, three performers open the show by assembling the disturbing, dark, squat figure of the narrator (perhaps the Cricket) from their gloved hands. Meanwhile, within a brightly-lit conical tent, shadow-play creates the illusion of puppet-maker Gepetto fashioning the life-size puppet from his magical piece of wood. The Blue Fairy materialises and floats effortlessly upwards as the tent morphs into her gown, all blue light.

In Geppetto’s workshop all eight dancers revolve around as figures in a clockwork musical box, each face a smiling mask, each body moving as precisely as clockwork as they rise in turn to the centre of their mechanical frieze, like paper cut-out dolls. Even the performers’ feet create ‘puppets’ and many hands make light work of Pinocchio’s nose.

The episodic nature of Pinocchio’s journey lends itself perfectly to this problem-solving teamwork. But of course the heart (beating rather than wooden) of the story is Pinocchio himself. Maria Doulgeri brings extraordinary physicality to the role, limbs revolving stiffly at first as if her joints are indeed awkwardly jointed with pins; flailing wildly and unnaturally to the scornful amusement of the nasty children in a playground who revel in excluding the little outsider; and gradually softening as he achieves empathy and selflessness – and so humanity.

The shape-shifting cast is uniformly excellent, equally at home as animals, puppet or humans, on the ground or in the air – or suspended on puppet strings. Scheming cat and fox are present and correct and banish any memories you may have of that Disney film.

The evocative music ranges from Shostakovitch to Beyoncé via accordion music from the Faroe Islands and the vocalising sighs and gasps from the cast add to the inclusive atmosphere. If some scenes are a tad long, the whole, at 90 minutes is just right. And it’s testimony to the show that despite there being no interval its young audience was spellbound throughout.

By Judi Herman

Pinocchio runs Friday 3 & Saturday 4 November. 7.30pm, 2pm (Sat only). £13, £8.50. Grand Theatre, Blackpool, FY1 1HT. www.blackpoolgrand.co.uk

Review: Grand Finale ★★★★★ – Apocalyptic vision in Shechter's triumphant total dance theatre

If that title sounds ominous, Shechter told me in interview: “I wanted to capture a sense of our time…that out-of-control feeling that things are coming to an end. And how can this have a happy ending?” * Plus, in a programme note on what he does – or does not – expect of his audience: “It’s about what is happening to them in their head, how they feel, [not about getting] it right in some way.”

These ideas coincide with news bulletins of refugees fleeing fresh violence and natural disaster to colour my response to what I’m seeing – figures in a stark, imagined landscape fleeing, falling, supporting each other’s bodies, dead or alive – often hardly noticing when they drop their burdens. Sometimes the flight is collective, sometimes one or two isolated figures move and pause in the shifting tableaux.

Shechter’s own original percussive soundtrack, with Yaron Engler, combines with Tom Visser’s harsh white lighting and the shadows it throws to add to the atmosphere of ominous apocalypse as screens like monoliths or tablets hide and reveal the dancers who also move them swiftly around the stage. These and the dancers’ fluid costumes are designed by Tom Scutt. It’s the first time Shechter has worked with a designer and it works triumphantly for this is total dance theatre.

The dancers also share the stage with a string sextet, the use of live music making another entirely successful first for Shechter. At first they are placed at one side, later they take centre-stage as the stark lighting gives way to something more golden, celebratory; but always they are part of the stage picture, even the choreography and design, as well as the sound.

That they are in formal evening attire is significant as they play ‘found’ music, notably Franz Lehar’s 'Merry Widow' waltz, 'Love Unspoken' (could that title be significant too?), as well as chamber music by Tchaikovsky and a Russian tune from Jewish composer Vladimir Zaldwich.

Although there’s room for lightness of touch and levity too, it’s perhaps that feel of early 20th-century Mittel Europa, between the wars, which brings to my mind the apocalyptic poetry of TS Eliot and WB Yeats. ‘Things fall part, the centre cannot hold’ writes Yeats in The Second Coming, though of course the dancers’ centres of gravity can hold – they are characteristically centred and grounded, unless they are ‘playing dead’.

Sometimes they recall the opening of Eliot's The Hollow Men: ‘We are the stuffed men / Leaning together / Headpiece filled with straw’. The poem closes with the famous lines ‘This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but a whimper’. Shechter’s triumphant apocalyptic vision ends rather with a bang – and a standing ovation.

By Judi Herman

Photos by Rahi Rezvani

Grand Finale runs until Saturday 16 September. 7.30pm. £12-£32. Sadler's Wells Theatre, EC1R 4TN. 020 7863 8000. www.sadlerswells.com

Then tours overseas: 1 – 4 November Danse Montréal; 9 – 11 November BAM, New York; 24 - 26 November Dansens, Hus, Oslo; 12 December Scène Nationale d’Albi

More dates to be announced

*see Jewish Renaissance Magazine July 2017 issue page 28

Review: The Red Shoes ★★★★★ - Bourne’s transcendent storytelling ravishes the senses

To Powell and Pressburger go the plaudits for moulding Hans Andersen's fairy tale with its hard magic into an allegory of art versus life. To Bernard Herrman the plaudits for writing film music that brilliantly conjures mood and emotion, atmosphere and character. And to Matthew Bourne with his creative team, led by designer Lez Brotherston and composer/orchestrator Terry Davies and with his close-knit family of dancers, goes the glory for taking all this magic and distilling it into two hours of transcendent storytelling that ravishes the senses.

To Powell and Pressburger go the plaudits for moulding Hans Andersen's fairy tale with its hard magic into an allegory of art versus life. To Bernard Herrman the plaudits for writing film music that brilliantly conjures mood and emotion, atmosphere and character. And to Matthew Bourne with his creative team, led by designer Lez Brotherston and composer/orchestrator Terry Davies and with his close-knit family of dancers, goes the glory for taking all this magic and distilling it into two hours of transcendent storytelling that ravishes the senses.

Filmmakers Michael Powell and Hungarian-Jewish refugee Emeric Pressburger met in 1939, at the London studios of Jewish movie mogul Alexander Korda. They formed a partnership that would produce lushly visual films with wonderfully-crafted stories, The Red Shoes, the magic realist A Matter of Life and Death, starring a dashing David Niven, the religious drama Black Narcissus, a vehicle for Deborah Kerr; and the time-travelling heroics of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (also starring Kerr, alongside Roger Livesey).

Bernard Herrmann was a giant among film composers, the go-to music man for Alfred Hitchcock, for whom he wrote scores including North by North West, Vertigo and Psycho. For Orson Wells he composed the music for Citizen Kane and for Truffaut for the dystopic sci-fi movie Fahrenheit 451. Now Herrmann is the go-to man for Bourne and Davies, who use music from Fahrenheit 451 and Citizen Kane and Herrmann's Oscar-winning The Ghost and Mrs Muir, as well as lesser-known, equally vivid Herrmann compositions. Davies' genius is in scoring the music for a small orchestra dominated by strings and keyboards, complemented by percussion, a glorious plangent sound that enhances mood and emotion, a gorgeous take on this period music that takes you into the world of men and women who live for their art.

A love triangle stands for the struggle between art and life. Aspiring ballerina Victoria Page succeeds in attracting the attention of ballet impresario supreme Boris Lermontov and becomes his protégée and his star – and the object of his affections. But she falls in love with his other protégé, gifted young composer Julian Craster – hence the pianos onstage as well as in the orchestra. Lermontov creates The Red Shoes ballet for Page, but its dark story of the shoes that force their wearer to dance to their tune proves dangerously prophetic as Craster and Lermontov face each other and Page struggles to balance her life in art with her desire for a real life.

The precarious balance between art and life is brilliantly realised by Brotherston's set – a grand pair of lush red velvet curtains, a proscenium arch framing the dancers in Lermontov's ballets, instantly conjuring period and cunningly conceived to swivel 90 degrees to reveal life backstage (complete with an audience mirroring us in our auditorium). Bourne and Brotherston brilliantly evoke mid 20th century dance companies, the tulle-clad prima ballerinas with their exotic 'Russian' names, the strutting male stars in tiny tunics atop tight white tights. Michele Meazza's Irina Boronskaja is a terrific star turn supported (literally) by Liam Mower channelling the likes of Michael Somes, Margot Fonteyn's partner before Nureyev leapt into her life. It's a clever, affectionate pastiche.

Into this effete world pirouettes Ashley Shaw's Victoria Page, a youthful whirlwind of ambition and talent. No wonder Dominic North's ardent Craster and Sam Archer's lordly Lermontov, so used to getting his own way, clash over her and what she comes to represent. This is such total theatre, that you almost think you have heard every word that passes between them, so vivid is the storytelling, so clear the allegory.

Bourne's recreation of the Red Shoes ballet is scarily exciting, graphically sucking in its heroine - and Page dancing the role. Brotherston's set is monochrome, a stunning homage to the avant garde of the period. The unsettling music from Fahrenheit 451 enhances the mood. We first see the red shoes framed by those proscenium curtains as the evening begins, lit so that Shaw wearing them is obscured. Now they seem to take on a terrifying life of their own, so that a tragic outcome to Page's story to mirror the ballet seems inevitable.

But meanwhile there are delicious delights to be had. Page's triumphant progress in the Ballet Lermontov takes her to continental France and the fun of dancers in bathing costumes playing beach ball. Her turn in a run-down East End music hall is preceded by a perfect - and perfectly hilarious - recreation of the Egyptian sand dance, complete with the eccentrics who created it, Wilson and Kepple (though not Betty, the girl who used to dance between them). And for us aficionados of music hall, the orchestra jauntily plays music hall standard Wot Cher!

Every member of the company clearly relishes creating multiple roles. And Brotherston's genius of course also extends to fabulous costumes that perfectly enhance the dance and play their part in the drama - the whole lit with a deep feel for every dramatic mood and moment by long-term collaborator Paule Constable. No wonder Bourne records his love and thanks to "the entire New Adventures family" in the programme. Their closeness and shared creativity achieve a total triumph.

By Judi Herman

Photos by Johan Persson

The Red Shoes runs until Sunday 29 January. 7.30pm (Tue-Sat), 7pm (15 & 26 Dec only), 2.30pm (Sat), 2pm & 7pm (Sun, except 25 Dec & 1 Jan). Sold Out (phone for returns). Sadler’s Wells, Rosebery Av, EC1R 4TN. 020 7863 8000. www.sadlerswells.com

Then touring: New Victoria Theatre, Woking, 31 Jan-4 Feb; Birmingham Hippodrome 7 - 11 Feb; Milton Keynes Theatre, 14-18 Feb; Theatre Royal, Norwich, 21-25 Feb; Theatre Royal Nottingham, 7-11 Mar; Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff, 14-18 Mar; The Mayflower, Southampton, 21-25 Mar; The Alhambra, Bradford, 28 Mar-1 Apr; Bristol Hippodrome, 4-9 Apr; New Wimbledon Theatre, 11-15 Apr; The Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury, 25-29 Apr; Theatre Royal Newcastle, 2-6 May; Festival Theatre, Edinburgh, 9-14 May; Curve Leicester, 16-20 May; Wycombe Swan, 13-17 Jun.

For further details and to book visit http://new-adventures.net/the-red-shoes/tour-dates

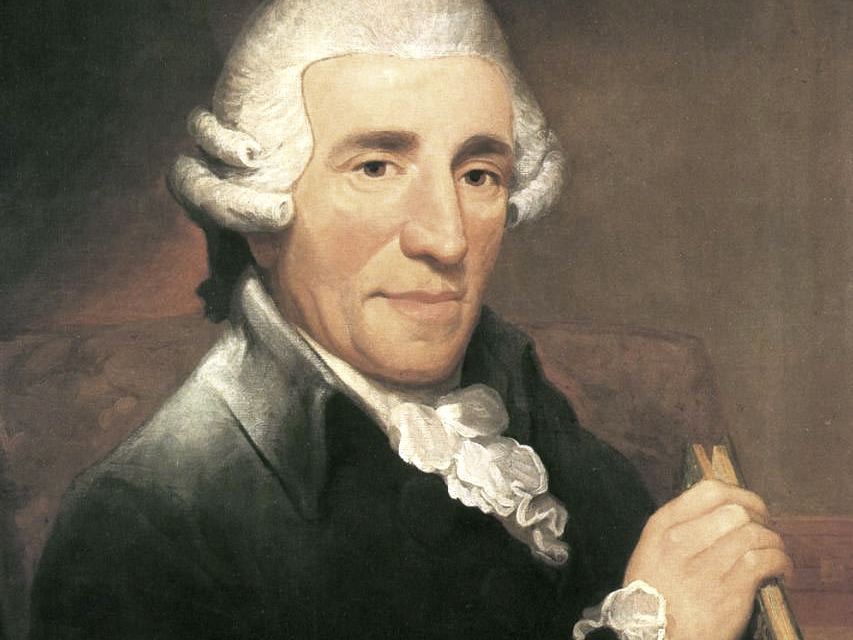

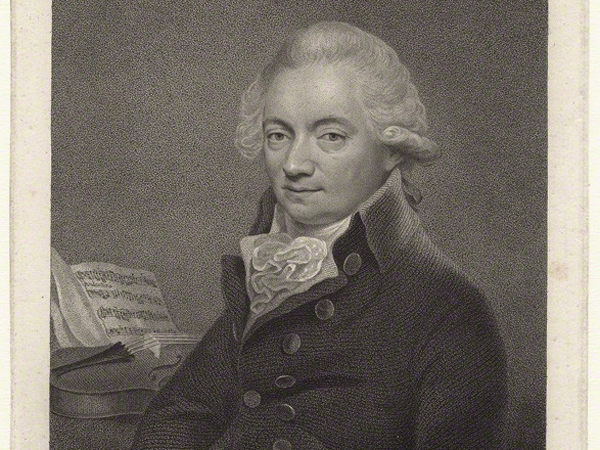

A look at the life of Johann Peter Salomon, the Jewish-born musician, impresario and creative force behind Haydn's Creation

Ballet Rambert’s new production – with 50 dancers and 70 musicians from the Rambert Orchestra onstage, soloists and chorus from the BBC Singers, and designs by Pablo Bronstein – marries dance to the soaring music of Haydn’s mighty oratorio and its beautiful libretto, taken from Genesis and the Book of Psalms, as well as Milton’s Paradise Lost. It comes to Sadler's Wells this month after a hugely successful premiere at Garsington Opera in July.

Ballet Rambert’s new production – with 50 dancers and 70 musicians from the Rambert Orchestra onstage, soloists and chorus from the BBC Singers, and designs by Pablo Bronstein – marries dance to the soaring music of Haydn’s mighty oratorio and its beautiful libretto, taken from Genesis and the Book of Psalms, as well as Milton’s Paradise Lost. It comes to Sadler's Wells this month after a hugely successful premiere at Garsington Opera in July.

These November performances of The Creation are elegantly timed for Jewish lovers of music and dance, as in synagogues worldwide we have just recently begun reading the Torah from the beginning again, with Genesis and the story of the creation.

A fascinating and little-known part of the story of the oratorio's creation is the role played by Johann Peter Salomon, German-Jewish-born musician, composer, conductor and impresario, in inspiring Haydn to compose the work. It was Salomon who provided Haydn with a libretto to draw on and refashion, that included those texts from the Bible and Milton. The pair seemed to have had a wonderful creative partnership, for Salomon originally brought Haydn to London, for the first time in 1791 and again in 1794. The symphonies Haydn composed specially for these visits are sometimes called the Salomon symphonies and as a violinist, Salomon joined Haydn to lead the first performances of many of the works he was inspired to compose in England.

Johann Peter Salomon was born in Bonn in the early 1740s into a family of Jewish musicians who thought it prudent for their infants' futures to baptise them. His sister Anna became renowned for her rich contralto voice and in Berlin, under the patronage of Prince Henry of Prussia, young Salomon composed several French operas with roles and arias for her to perform in concert.

Salomon was invited to Paris in the early 1780s and then to London, where he really found his niche. So much so that in 1790 he decided to visit Vienna to invite both Haydn and Mozart to come to London. It seems that both accepted, but sadly Mozart died in 1791. Haydn earned several hundred pounds and huge public adulation for the music he composed and played in London - imagine how the late Leonard Bernstein or Stephen Sondheim, Leonard Cohen or Bob Dylan would be feted if they, came to London to premiere compositions especially composed for Britain.

It's said, however, that Haydn refused to pay his orchestra and Salomon had to pick up the bill, which he did with a good grace. Unsurprisingly, Salomon's Jewish origins meant he was regularly accused of being mercenary, even though many regularly took advantage of his good nature. When he was called a Jew, it was of course a derogatory term. Yet by all accounts he had a winning personality, which made him popular with patrons and fellow musicians wherever he went. The gifted musician clearly had a good head for business too, a dream combination for an impresario.

Salomon went on to become one of the founder members of the Philharmonic Society and led the orchestra at its first concert on 8 March 1813. Salomon died in London in 1815, of injuries suffered when he was thrown from his horse, and is buried in Westminster Abbey. In 2011 the Royal Philharmonic Society instituted the Salomon Prize “to highlight talent and dedication within UK orchestras.” A fitting tribute indeed.

by Judi Herman

The Creation runs from Thursday 10 – Saturday 12 November, 7.30pm, £12-£45, at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, Rosebery Avenue, EC1R 4TN; 020 7863 8000. www.sadlerswells.com

Two consecutive evenings, two talented young Israeli performing artists, both with so much to offer

I rounded off October by spending two consecutive evenings being excited and challenged by the work of two talented young Israeli performing artists, both with so much to offer. Niv Petel is heartbreaking in Knock Knock, his beautifully nuanced account of a devastating situation faced by too many Israeli families, and Hagit Yakira attracted full houses for her exciting new work Free Falling.

Petel is an extraordinary physical actor, wonderfully convincing as a devoted mother whose son is the centre of her life. An engaging and important contribution to our understanding of life in Israel. And at Sadler’s Wells last week, dancer/choreographer Yakira presented four talented performers falling and recovering again as they take what life throws at them. Supporting each other, their eyes and faces as important as the rest of their bodies as they look out for each other. In a beguiling add on, three more dance artists responded to Free Falling – including full audience participation on the studio floor, everyone linked in a joyful dance – a sort of Hora at Sadler’s Wells, which makes Israeli dance so welcome. Niv Petel and Hagit Yakira are certainly names to watch.

Continue through the blog to read our reviews of Knock Knock and Free Falling, as well as an interview with Niv Petel, or click the names to go straight to each one.

by Judi Herman

A Report on Free Falling, the new show from Israeli dancer/choreographer Hagit Yakira at Sadler’s Wells

Hagit Yakira attracted full houses for her exciting new work, four talented performers falling, recovering and supporting each other, as they take what life throws at them. Their eyes and faces are as important as the rest of their bodies as they look out for each other. Yakira says she invites her audience “to experience the unravelling of real life experiences”. What I loved, though, was the synthesis – the building up of the elements that make up this seemingly simple but actually complex work performed on a vast bare stage.

One eloquent male dancer repeatedly falls and rights himself, while uttering the words "fall" and "recover". He’s joined by a second male dancer, full of solicitude for his partner, whom he repeatedly lifts and allows to slip away. A female dancer joins them and composer and multi-instrumentalist Sabio Janiak adds his serenely plangent music to the mix. A second female dancer makes a quartet and all four display the same solicitude for whichever of them is falling – clearly making recovery possible, not just by supporting them physically, but with the empathy in their expressions. I thought of the motto of the Three Musketeers (with D’Artagnan also four of course): “All for one and one for all”. The space is vast but they crisscross through it all. Janiak adds percussion too – and sometimes takes away his music leaving just the dancers in their loose, pastel clothes. It's moving, telling, soothing, startling and always engaging. The dancers are Sophie Arstall, Fernando Belsara, Stephen Moynihan and Verena Schneider.

In a beguiling addition, three dance artists respond to Free Falling – a different trio each night. The night I went there was a considered response from Dr Emma Dowling on video and an immediate response from Rosemary Lee, a choreographer and creator of extraordinary large-cast community pieces for dancers of all ages. It was fascinating to compare Dr Dowling’s conscientious onscreen response with Rosemary’s joyful movement through the space, retracing the footsteps of the dancers and throwing down pages from her notebook in response to what she had seen and experienced in each spot.

Between these two came the response from dancer Rachel Krische, drawing on the movement quality choreographed by Yakira for the quartet, but relating to members of the audience – using them as her dance partners, first touching, then asking for more – for support and the intertwining of limbs. And finally, gloriously climaxing in full audience participation on the studio floor – everyone linked in a joyful dance – a sort of Hora at Sadler’s Wells, which makes Israeli dance so welcome. Hagit Yakira is a name to watch – and JR will be watching out for more Israeli dance at Sadler’s Wells.

By Judi Herman

Photos by Loy Olsen and Kiraly Saint Claire

Free Falling was presented as part of Wild Card, a series of specially curated evenings at Sadler's Wells Theatre from a new generation of dance makers, bringing fresh perspectives to the stage. www.sadlerswells.com

To read more about Hagit Yakira and Free Falling, click here http://www.hagityakira.com