A model cemetery made of paper cutouts, neon mezuzot and a klezmer cantata are some of the projects on show in Kaunas to mark its role as European Capital of Culture 2022

Lithuania’s second city, Kaunas, has often lived in the shadow of the country’s capital, Vilnius. But this year, it is the European Capital of Culture with hundreds of events taking place across the city. Part of the culture festival will include a long-overdue recognition of Kaunas’ rich – but often dark – Jewish history.

Before World War II, Kaunas (formerly called Kovno) had a Jewish population of about 40,000 – around a third of the city, which was enough to sustain synagogues, schools, a prison and five Jewish newspapers. But most of Kaunas’s Jewish life was destroyed in the Holocaust and its memory erased during the Soviet era, something that is being explored through several Capital of Culture events.

“We want to reflect on the city’s identity, history and our relationship with the past,” explains Dr Daiva Price, curator of the Memory Office section of the programme, which is addressing Kaunas’ Jewish past, among other forgotten histories.

Visitors at the William Kentridge exhibition © Martynas Plepys

“We aim to fill in some of the gaps and to break down the stereotypes from the Soviet era, when Kaunas was presented as the most Lithuanian city. We want to remind ourselves and Europeans that Kaunas has always been a multiethnic city,” she says, noting the importance of talking about the Holocaust’s victims. “It is vital for us, as the heirs of this city, that their memory never fades away. Most of our programme is dedicated to this Jewish memory and a lot of our projects address the issues of the Holocaust.”

The country has long been accused of avoiding discussion of its part in the destruction of Lithuanian Jewry, and Kaunas (like other cities) still has streets glorifying 23 June 1941. On that date, the Lithuanian Activist Front and other nationalist groups slew hundreds of Jews within hours of the Nazi invasion.

That wave of pogroms fed into the subsequent genocide in which the Nazis, with the aid of local collaborators, exterminated 95 per cent of Lithuania’s Jews – the highest murder rate in the Holocaust. In Kaunas, thousands were shot and thrown into mass graves at the Ninth Fort on the outskirts of the city.

Jenny Kagan’s First Date Case from Out of Darkness, from its first installation in Halifax, 2016

Among the projects addressing this past is Out Of Darkness (4 August to 30 October), an installation by British artist Jenny Kagan based on the experiences of her parents. They met in Kaunas and survived the Holocaust by hiding, with her grandmother, in a tiny space in a factory attic. “The installation is in a massive complex of buildings and is a fully immersive experience,” says Kagan, who has also created a new cantata for a musical commission by South African composer Philip Miller, featuring multiple stages and performers, including a klezmer band.

The South African artist William Kentridge, whose great grandparents sailed from Lithuania to Cape Town in 1900, also has an exhibition at the National Art Museum, That Which We Do Not Remember (until November). Its focus is a moving audio installation with loudspeakers playing a soulful lament by South African choral singers set against the backdrop of an abandoned Jewish cemetery made with paper cutouts.

Other events include an exhibition at Kaunas Photographic Gallery (1-31 October) celebrating the work of street photographer Dorothy Bohm, who lived in Lithuania before leaving for England in 1939.

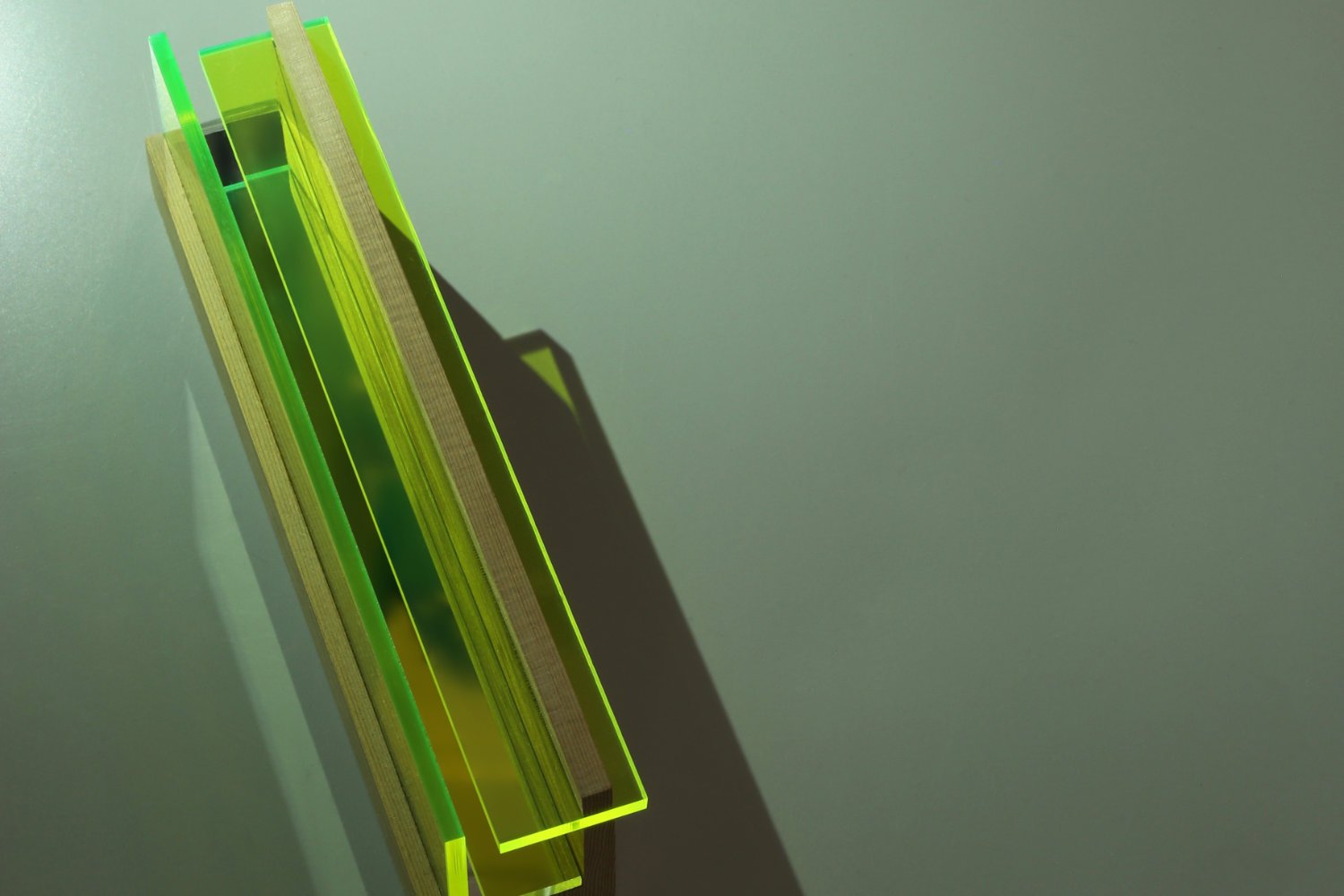

Mirror Tzohar Threshold © Jyll Bradley

For a sense of Kaunas’ bustling pre-war Jewish life, visitors can head to the Maironis Museum of Lithuanian Literature, which is showing Mausha Levi and Shimon Baer – The Legacy Of Interwar Photographers (2 August to 1 October); and Window To Jewish Life In Kaunas Before The Holocaust, at the Kaunas Multicultural Centre (25 September to 15 December).

Another project, Threshold (from 18 July), by British artist Jyll Bradley, involves the creation of 22 tiny sculptures modelled on a mezuzah, which have been placed on buildings with Jewish history. “The process is as important as the actual pieces, as each one involved a conversation with building owners,” says Bradley. “The work includes an audio guide in English and Lithuanian, with information about each building, as well as discussion of the meaning of the mezuzah and what it can teach us.”

By Peter Watts

Header photo by Martynas Plepys

To find out more abou tthe European Capital of Culture 2022, see kaunas2022.eu/en/litvakforum.

This article appears in the Summer 2022 issue of JR.