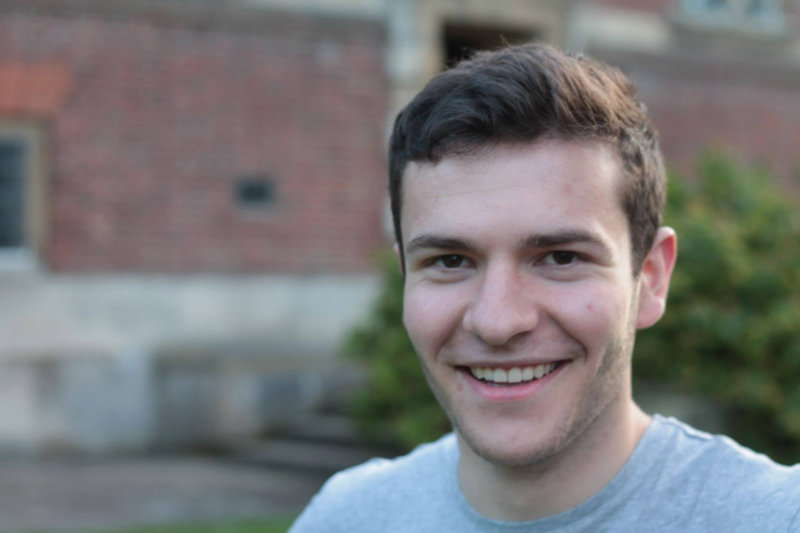

Manchester-born filmmaker Gary Sinyor makes his theatre debut with NotMoses, an irreverent retelling of the Exodus story – starting with the baby the Princess leaves floating on the Nile when she spots Moses, a nicer baby. NotMoses grows up a slave in Prince Moses’ shadow, until God orders both of them to lead the Israelites out of bondage – though it takes feisty Miriam to actually lead the Exodus. Think Life of Brian meets The Ten Commandments, which Sinyor says is a comparison he hears often.

Manchester-born filmmaker Gary Sinyor makes his theatre debut with NotMoses, an irreverent retelling of the Exodus story – starting with the baby the Princess leaves floating on the Nile when she spots Moses, a nicer baby. NotMoses grows up a slave in Prince Moses’ shadow, until God orders both of them to lead the Israelites out of bondage – though it takes feisty Miriam to actually lead the Exodus. Think Life of Brian meets The Ten Commandments, which Sinyor says is a comparison he hears often.

"I think it's because there is only one other biblical comedy, Mel Brooks’ History of the World. But it is more like The Life of Brian because History of the World went through the ages and this is very much centred on the Exodus from Egypt."

Might this do for Moses what The Life of Brian did for Jesus?

"This started life as a film script and I may make it as a film at some point in the future. Unlike The Life of Brian where you’ve got one character, I sort of knew I needed to have Not Moses and Moses. In a sense, philosophically as well, I knew I wanted to have God in the play. So I knew there were certain things and a couple of scenes that I wanted to do from the off. And then I just had a huge amount of fun writing it. It’s not quite a parody of The Ten Commandments but if you take that film, which has Moses, the Princess, Pharaoh, Rameses, you’ve got certain obvious characters that come to mind. And I knew that I wanted to have Not Moses, a slave in the background of the story in Bible terms, very much in the foreground of the story in this play. You’re looking at the story of the Exodus from the point of view of those slaves in the background, not from the point of view of Moses, who was at the Palace enacting things with Pharaoh. So it’s that dichotomy of having two different families, the slave family in the foreground with the Moses story on the side."

So how did it get to be a play in the theatre rather than a film, when you’ve always been a filmmaker?

"About a year ago someone said to me 'you should do it as a play' and I thought, you’re right! I’m constantly going to the theatre, it’s such an exciting medium, always sold out and quite often people are laughing uproariously. And quite often I go to the cinema and there’s no one sitting in there two weeks after the film has opened. And it goes to DVD and it’s on Netflix very quickly and you’re not experiencing the same amount of fun. You see theatre shows like The Book of Mormon and Spamalot that have longevity, and for me this story was too funny and too interesting - and potentially a bit challenging – to see disappear after a couple of weeks in a cinema."

It sounds as if you’re going to want to be there every night so you can hug yourself when the audience laughs…

"I was planning on it but I’ve been told in no uncertain terms that the actors would not be jumping up and down to have the director there every night. I may well have to go in disguise. But it’s an extraordinary experience to be in a cinema or a theatre and hear the audience responding to something. So although I am sure I won’t be there every night, I might dress up in disguise on occasions."

My mind is boggling, what will you dress up as? If Moses – or NotMoses – you would be noticed! So it’s a bit like Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, where two minor characters from Hamlet take centre stage and Hamlet himself soliloquises away in the background?

"The Moses story is there. I shouldn’t call it a bastardisation, a clear retelling or reinvention of the Moses story is there but for me it was important to have a Not Moses – he’s like an atheist, he doesn’t believe in God and he wants to lead the Children of Israel out of Egypt without the help of anyone else. He says ‘we should just get out, go!’ and no one listens to him because people are waiting for God to perform miracles. So, if you like, he’s the rebel slave hanging around in the background of the biblical story. Because I am sure there were people saying ‘let’s get the hell out of here during those two hundred odd years. People rebel and that was one of the things I wanted to tackle. The Bible is itself really weird on this. We have a point of view of what these slaves were doing and what they looked like almost from art and the film. The truth is they left with gold and silver and they seemed to have flocks and cows and it’s difficult to get a handle on what kind of slaves these were."

It’s obvious you’ve read the Torah, checked out the portions. Did you have the sort of upbringing where that’s a given?

"We come from a Sephardi background and we used to go to Synagogue every Shabbat. And I used to read that portion from the Hertz Chumash in English year after year until I was 16 or 17. So it sort of engrained itself. And when I started going again when I was older, I read it again. And at times I read it with an uncritical eye. At one point I did a Project Seed thing and was sold on what they’re trying to do (‘Seed provides adult and family Jewish education across the UK through formal study and informal experiences. We aim to strengthen the family through positive Jewish encounters and by sharing the richness of Jewish life, learning and values’ – from Project Seed website) I thought okay I’ll take that leap of faith and then I undid that leap of faith and now when I go to synagogue I do look at it with a more critical eye."

Your God is emphatically He with a capital H, but then Miriam is not just playing a supporting role, she’s playing a leader’s role. Tell me more about her. It sounds as if God and Miriam are the partnership leading the Children of Israel out of Egypt.

"Miriam comes into the play more and more as it goes on but she is a feminist – not even a feminist, she is just a fighter for equal women’s rights in a very patriarchal world. And even the other women in it are like; ‘shut up and make the soup’. She is very much - and I stress this is a comedy - an early forerunner of the fight for women’s rights, within not just religion but generally. And she probably has the strongest speech towards the end of the play, which lays out a position, more or less in front of God. People do challenge God. There are scenes where Moses does that in the burning bush story in the Bible. He says ‘who am I?’ and I have just taken that a lot further."

I love that you take it seriously as well, though the press have stressed the comedy and irreverence. It sounds as if there are a lot of laughs but it’s not just sending it up.

"No, in a weird way it’s very difficult. You have children and you like the idea of bringing them up in the Jewish religion. We’re caught up in incredibly difficult times and I want my children to be brought up with a cosy, Jewish, lovely warm environment, which offers a two-year old and a nine-month old Hannukah and it’s marvellous and the memories one has (of Festivals) from Passover to Sukkot are all amazing. But I think if one’s talking about the truth behind these stories, then I certainly think that some of that is challenged by the context of the play."

Do you belong to a synagogue?

"We belong to New North London but because I am Sephardi I also go to the Persian Community at Kinloss. So we alternate between the two, if I go out of the house and turn left I go to New North London, if I go right it’s Kinloss."

You’ve said the audience has a role to play in your show as the Children of Israel…

"When I adapted it from a film into a play, it was a joy. For example in the film I’d been talking to people about how you create 600,000 0r three million people, so there was that whole CGI thing and I was having conversations very seriously about how to make it as a film. When I came to the play I thought, how am I going to do that? I’ll just turn the audience into the Children of Israel! They will experience, for example being harangued by a taskmaster and the 10 plagues will be experienced in some way shape or form that I am not going to go into …! So there is that inclusive quality that theatre offers you and at some points the fourth wall will be broken. I did have a couple of read-throughs previously, after doing workshops on it with the cast and it was extraordinary. We had 20 people who were laughing uproariously. So the idea of having 350 is even better. And I think it will be cinematic as well, it’s not a static play. It has nine members in the cast, down from 600,000."

The Arts Theatre has a good track record of getting lots of people laughing at Jewish humour, with Bad Jews for example, doesn't it?

"It’s a really lovely theatre and they’ve got Ruby Wax coming there in January, which is interesting as well; and more than anything else they are just so enthusiastic to have the play there and give it a ten-week run, which for a new play is really quite extraordinary."

Jews are good at laughing at themselves – I guess they can laugh at religion too?

"I think we can, but I’d be mortified if Christians and Muslims and atheists didn’t come along as well. It’s not like only Christians went to see The Life of Brian. There is something underneath this which well, is just funny, but hopefully it applies to people across the Abrahamic faiths and beyond. It won’t be a solely Jewish cast and it won’t be a solely white cast. So we are doing our best to make it appeal across the board and make a point at the same time."

You’re playing over Purim and Passover – it’ll be like a Purimspiel for Purim.

"Yes we are playing over Purim which will be an exciting night I think. And I have said to the theatre that they should kashrut the bar over Pesach (Passover) and they should certainly be selling matzah sandwiches of some sort. And I haven’t pointed it out to them but they certainly won’t be selling many beers. And yes it’s certainly playing over Purim. Seder night will be difficult, certainly the first night. I think they’ll be marketing to anyone except the Jewish audience that night. Who knows about the second night…"

Second night Seder at your play perhaps?

"There is a Seder in the play as well, the leaving from Egypt."

Actually it might have quite a resonance because it’s so timely, as it’s playing at the right moment running over Passover.

"Yes, it’s the best slot I could have hoped for. Well, I could have hoped for it about five years ago, that would have been good as well."

Manchester does seem to be a hotbed of Jewish creativity, what with Nick Hytner Howard Jacobson and Jack Rosenthal, to name but three.

"I think there is something about Manchester that is very different from London. My children are being brought up in London. Every time I go back, which I do four or five times a year, it does remind you you’re outside of it in a way you’re not in London. In fact the Jewish family in Not Moses that Not Moses is brought up in are going to be talking with Manchester accents."

So they’re 'provincial’ in other words. You must be saying it’s a plus factor too?

"Oh it gives you creative inspiration. I lived in Los Angeles for a while, where they’re only going to come up with stories about valet parking – they have no angst to build on. Angst is a crucial part. And there’s more angst in Manchester than in London I think – or there could be more in Leeds – I wouldn’t want to claim the crown."

By Judi Herman

NotMoses runs Thursday 10 March – Saturday 14 May, 7.30pm & 2.30pm, £19.50-£69.50, at the Arts Theatre, Great Newport St, WC2H 7JB. http://notmosesonstage.com