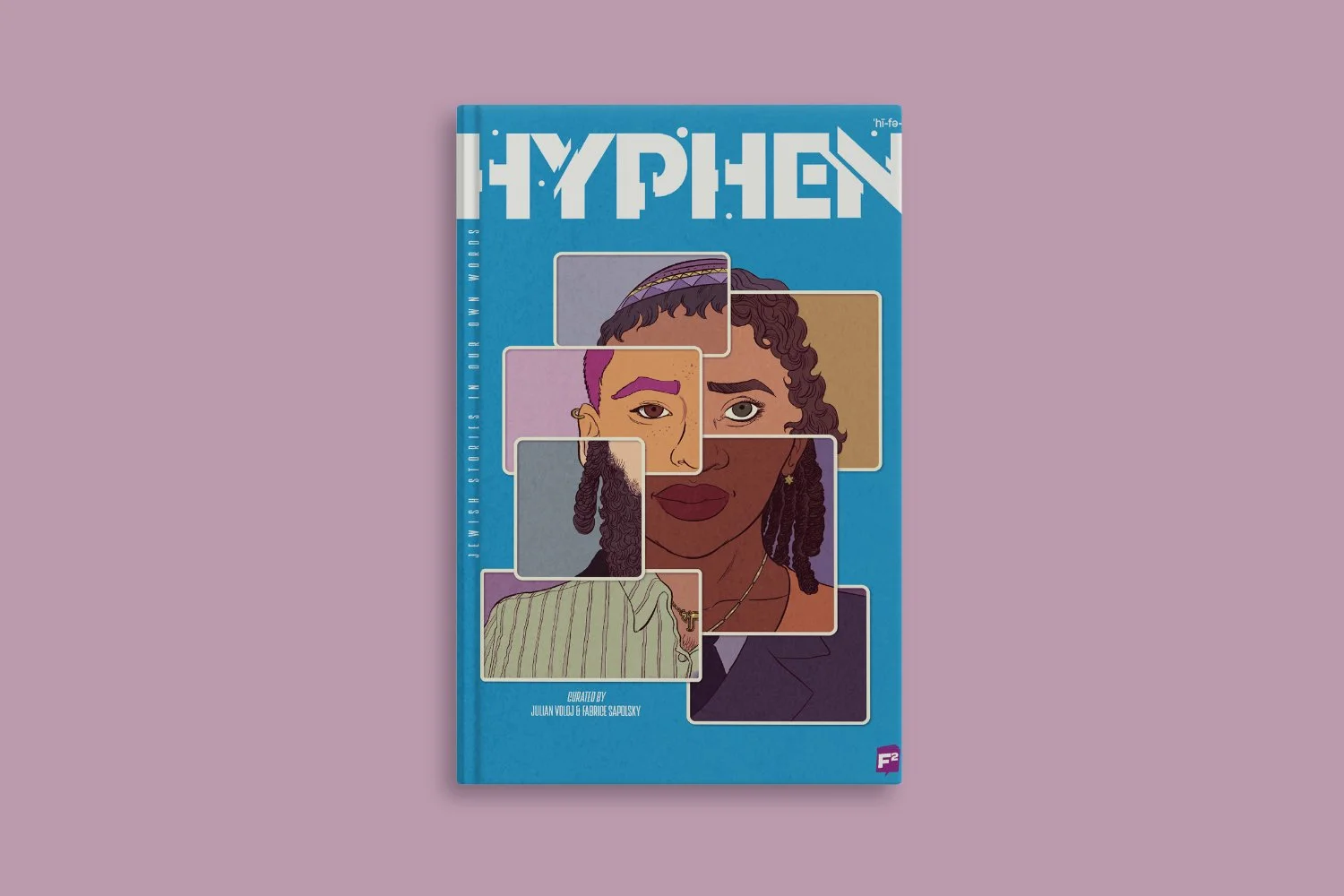

A new graphic anthology celebrates the rich diversity of the Jewish experience around the globe

When Julian Voloj and Fabrice Sapolsky began assembling the 12 stories that make up the extraordinary graphic novel Hyphen, they were thinking about the stories that are often left out, the stories of Jewish communities in Africa, India and East Asia. The way Jews from far-flung diasporic communities look at each other, and the assumptions made by both our host countries and by ourselves. Recently, I attended an event they held in New York with contributors to their collection.

Voloj, born in Germany to Colombian parents, is the executive director of Be’chol Lashon, an organisation dedicated to celebrating ethnic and racial diversity within the Jewish community, as well as the author of several graphic novels. His co-editor, Sapolsky, a French-American artist and writer with both Ashkenazi and Sephardic roots, is the co-creator of Spider-Man Noir and founder of FairSquare Press. Comics were their chosen format, not only because this is the form both practice in their own creative work, but because the graphic novel can be a link between prose and film. Helpfully, you have more control in a graphic novel than when making something for the screen and an infinitely more manageable budget. And, as Sapolsky said about the form, “there are no limits to it”.

Many of the stories in Hyphen are about immigration and information hidden from children, stories of trauma, the experience of being a refugee. In matching storytellers and artists, the editors tried to find Jewish artists, initially, but that wasn’t always possible, especially given tight deadlines. However, fortuitous links happened. For example, the editors knew of an Italian-African artist who wanted to work with a black storyteller, so paired them with Shoshanna, the trailblazing first female rabbi of Uganda’s Abayudaya community.

Most graphic novels are only one year in development. An indication of the care taken to assemble this one, is that the editors and their publishers Fairsquare Graphics, spent three years bringing it to completion.They wanted everyone to feel accurately represented: that style needed to be appropriate to storyteller and images should be balanced and faithful to the culture of the narrator. For the Jewish history of a kimono, “the story screamed manga”. Uzbeks change shoes to socks indoors, Jewish women of Mumbai wear green bangles to signal they’re married, and in Uganda the sound of drums welcomes Shabbat.

Sapolsky described how his Algerian aunt felt that because she had no children and hadn’t accomplished anything, her life was diminished. Fabrice replied to her, “no, you are a witness”, and the act of witnessing is at the core of each of the twelve stories. As Eddna, from Mumbai said, she was interested in passing down the stories of a little known group within a marginalized community, and telling her story was “my legacy”.

Haftam, from Ethiopia, was asked how it felt to have your life represented in a comic. She explained the first comic she read was X-Men, but she never thought she’d be in one, and in telling her story had to think about how it would fit into that medium. Her husband encouraged her to do it, before her parents, an older generation of witnesses, were no longer around to tell their stories. The act of writing was intensely emotional for Haftam and exposes uncomfortable truths about the difficulties of integration: one of the most searing moments in the book is when she and her mother are nearly run over in a market in Israel, the driver screaming at them to go back to Ethiopia.

As Voloj said, “these are stories of overcoming adversity and celebrating life”. Hyphen is a much needed testament to the existence and survival of diverse Jewish communities, and we hope there will be more volumes in the future.

By Susan Daitch

Photos courtesy of Global Jews

Hyphen: Jewish Stories in Our Own Words curated by Julian Voloj and Fabrice Sapolsky, Fairsquare Graphics, 2025, $25. globaljews.org/hyphen